Hasta in Manipuri – Part 1

#WednesdayWisdom is a series that began during the 40th anniversary celebration of Akademi to revisit Indian classical dance roots by sharing gems of knowledge from ancient Shastras (dance texts) that hold relevance even today. The blog is curated by Bharatanatyam artist, Suhani Dhanki, along with with our Head of Marketing, Antareepa Thakur.

In this blog series, we are inviting artists practicing different South Asian dance styles to contribute some interesting facts about their art forms, some of them rarely seen in the UK. Read our previous blogs in this series here.

This blogpost on Hasta in Manipuri is researched and written by Debanjali Biswas, a scholar of social anthropology and performance studies and the co-director of performance collaborative – Mitradheya. She is a Manipuri dancer trained in the style of Oja Bipin Singh and is based in London.

Designed by Apollonia Bauer.

In Manipuri dance, the word for ‘hasta’ or ‘mudra’ is Khut-thek; khut means hand and thek is for gestural movement in Meiteilon, or Manipuri language. Khut-thek is mostly paired with the word jagoi – the word for dance. In the context of dance, Jagoi-khut-thek means ‘movements of hands’, in the context of ritual it means ‘offering of movements’.

The classical dance of Manipuri was born out of rituals that are danced by the Meitei community residing in Manipur, India. The style of Manipuri that we see on stage is a confluence of traditions that are associated with four rituals. These rituals are observed as devotional service, or rites of passage, or propitiation rites, or all. Dance is derived from each of these rituals – Lai Haraoba, Huyen Langlon, Nata Sankirtana and Raaslila. These dances are considered as genres of Manipuri dance, alongside being integral part of Meitei social fabric. However, the classical Manipuri tradition is often associated with only the Raaslila tradition (which is debated by different institutions).

Broadly, the origin and development of movement has passed through four distinct stages – modern India, post-Vaishnavite period beginning in late 18th century, Meitei indigenous faith as found in oral traditions and few texts, and a phase which exists beyond perceptible time i.e. local lores and myth. The history of Manipuri dance and contemporary renditions are connected to each of these stages. Nata Sankirtana and Raaslila emerged in the post-Vaishnavite period – Huyen Langlon and Lai Haraoba are rituals that are reminiscent of the indigenous, local faith and which are not seen outside the Meitei community. A student of Manipuri is expected to have a strong foundation in the vocabulary and grammar of all dances that are derived from these four rituals, even if they may specialise in only one.

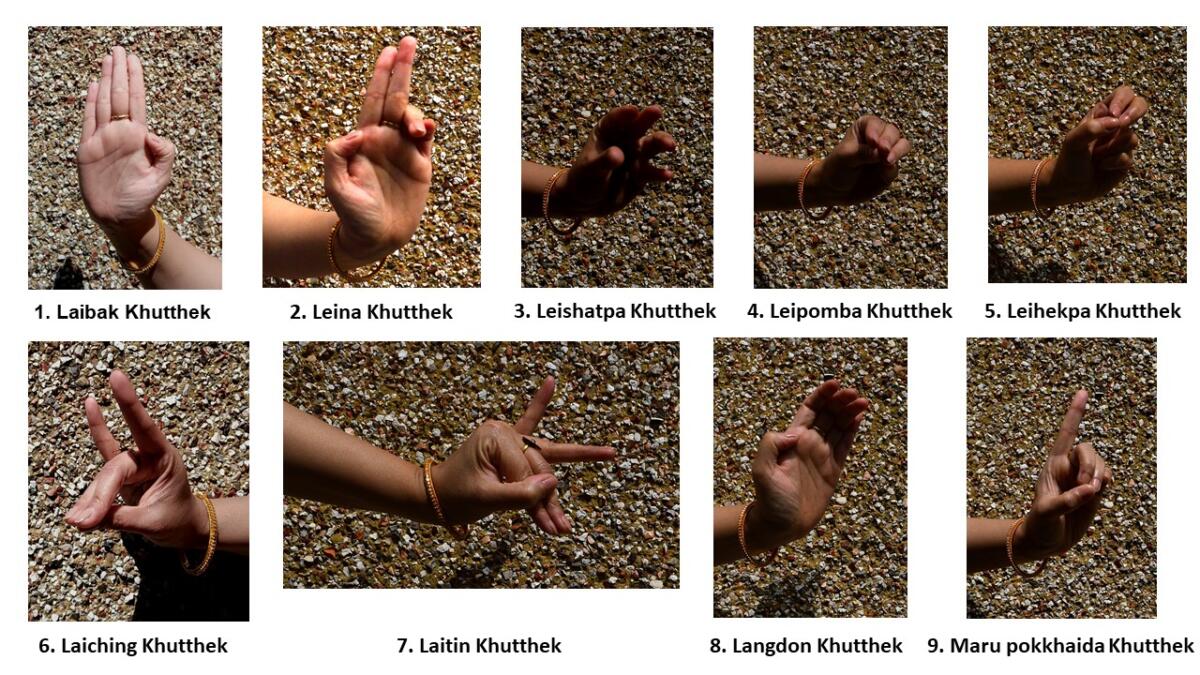

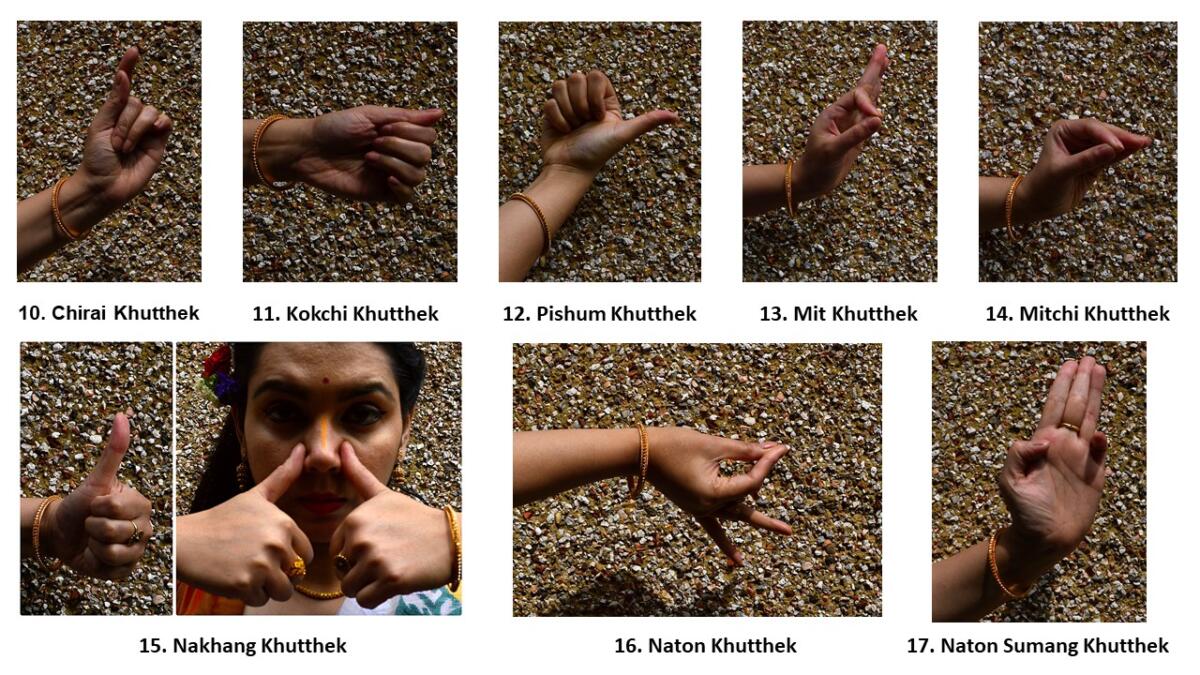

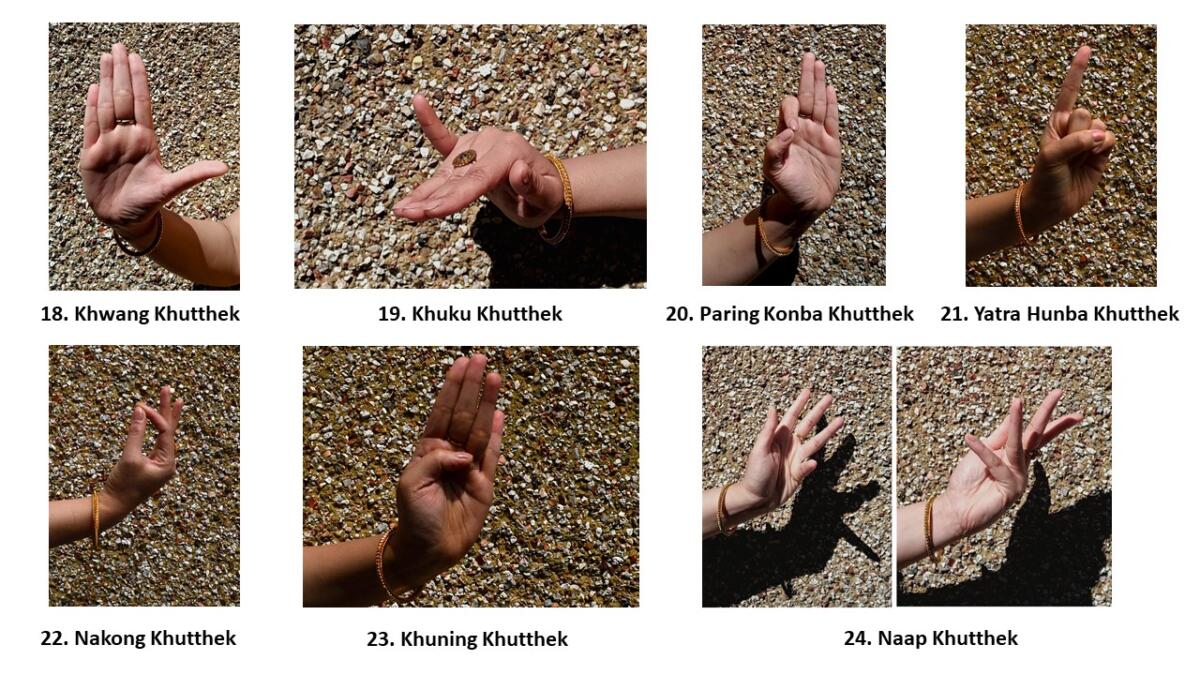

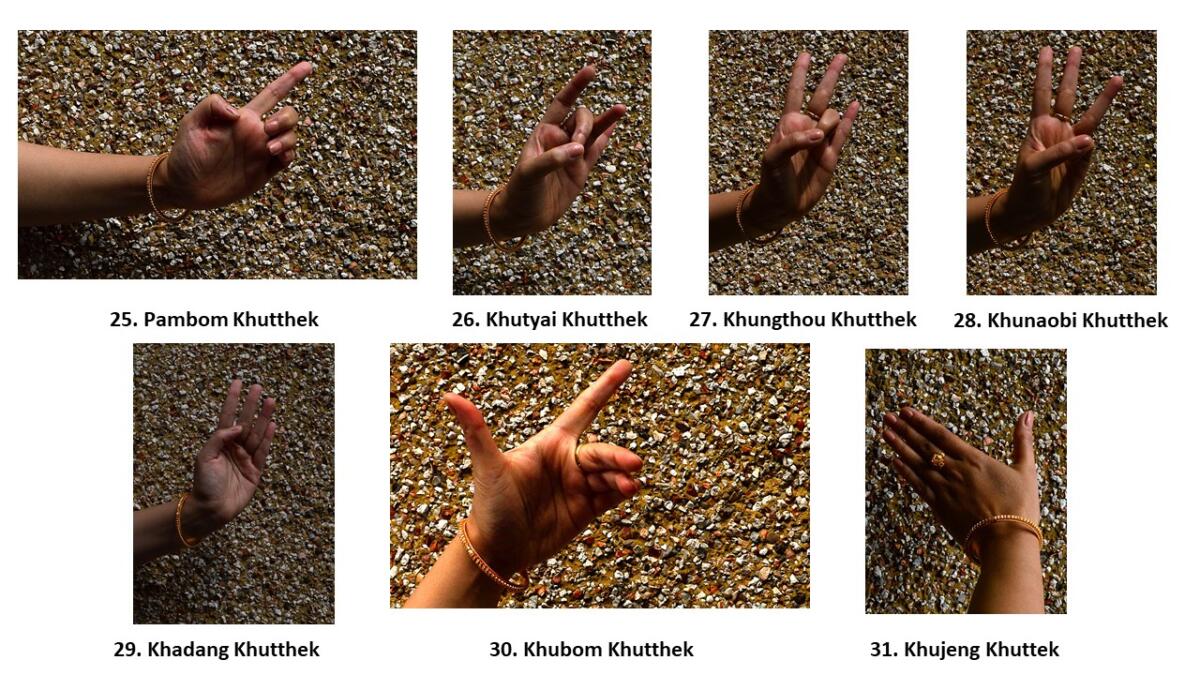

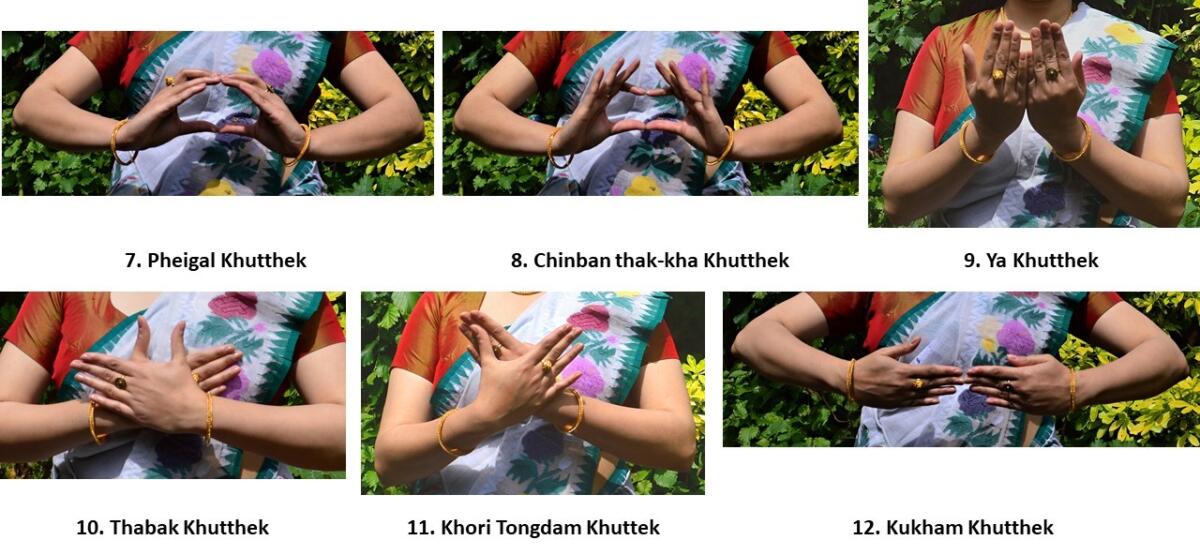

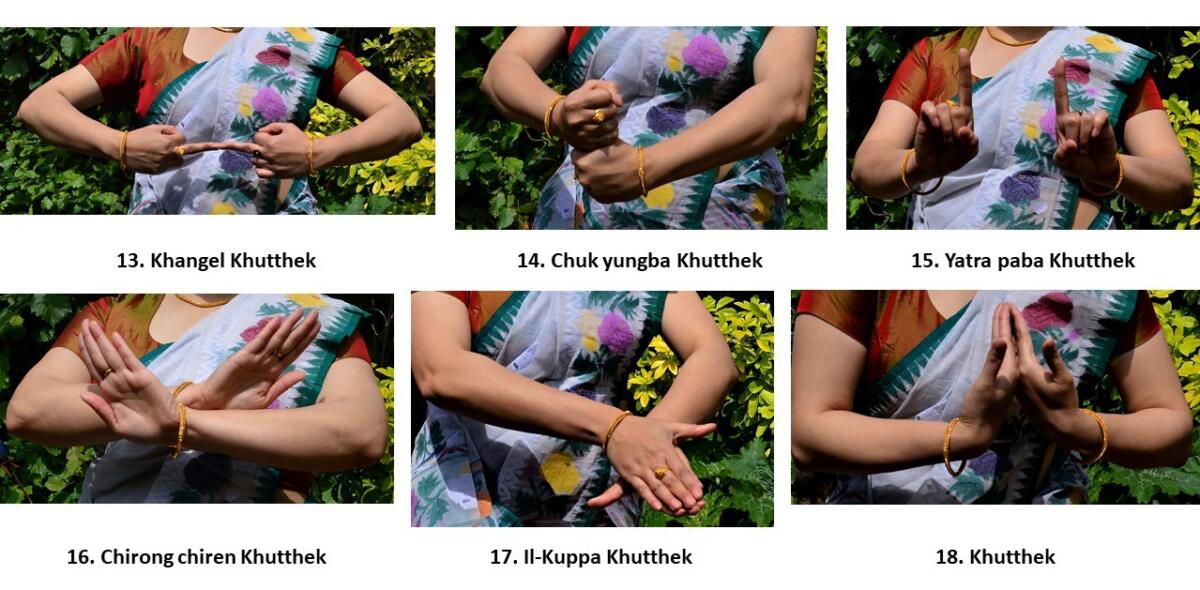

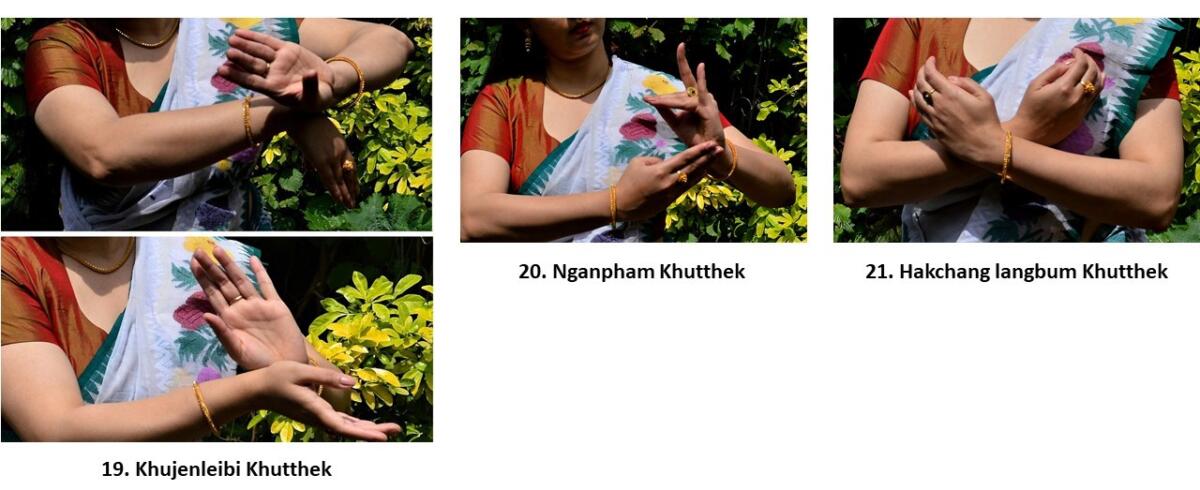

In this segment, I will introduce khutthek as observed in Lai Haraoba and Huyen Lanlong rituals. These are the core hand-gestures that later emerge within Vaishnav traditions as well. The single-handed and two-handed gestures as codified and named in Hindangmayum Thambal Sharma’s book Jagoi-Khut-Thek accompanies this article.

For centuries, the dances did not follow any text and the grammar of dance has been transmitted kinaesthetically and orally. Mention of gestures are however found in descriptions of movements in vernacular song texts such as Anoirol (language/art of movement), Panthoibi Khongulon (footsteps of goddess Panthoibi), Leishemlol (lore of creation). Through his analysis of manuscript of Anoirol written in old Meitei language, Meitei scholar K. Yaima describes finger-gestures as Anoiba, and the co-ordinated movement of limbs and the body as Noiba. Each of these sung texts describe movement and gesture as slow, fluid, almost contemplative and exploratory rather than fixed. This is seen in subtlety and restraint in hand and facial expressions even today.

Single-handed Gestures

Hand Gestures in Lai Haraoba:

Practitioners and scholars emphasise that hand gestures flow continuously from one to the other. Stillness or fixity of khut-thek is not really a distinguishing characteristic of Manipuri and have only developed in recent choreographies. The body in dance in Meitei philosophy is an amalgamation of physical, intellectual, cosmological bodies. The emphasis on various functions of the body – such as flow of movements, dexterity in performing tasks, agility, sexuality, sharing a relationship with nature, being a part of community – are described with hand gestures in the Lai Haraoba. In general, the ritual is performed over a few days mainly as a propitiation rite for Meitei divinities or lai. One of the major sequences is called Laibou Jagoi.

In Laibou Jagoi, the ritual participants are led by the Amaibi (priestess) and Penakhomba (balladeer) and supervised by Amaiba (priest). The ritual begins with Laiching Jagoi – the Amaibi gesturally infuses soul into the lai by touching her own navel with one hand (khoidou khutthek) while gesturing the thread of life by the other hand (laiching khutthek). It is followed by the Hakchang Sagatpa (the making of the body) which is danced with laibou khutthek humphu-mari or 64 hand gestures. The Amaibis use simple single-handed or two-handed hand gestures to describe the formation of a human body inside the womb. The first gesture is for the navel, and the sixty-fourth is for the soul that is infused in the body. In between, the limbs, the crown of the head, tip of the toes, genitalia, blood, muscle, skin, nerves are shown with hand gestures. The Amaibis touch each part of the body as they call it out while circumambulating the ritual space anti-clockwise. Following Hakchang Sagatpa, 300 hand gestures describe the individual’s growth from its infancy to adulthood. Amongst others, these include the mother at birth (Nungnao Jagoi), construction of a residence (Yumsharol), seeking out lovers (in Panthoibi Jagoi), agriculture and cotton planting (Pamyanlon), Preparing threads and cloth (Phisarol), fishing with trap (Longkhongba). These 364 khutthek are gestures without which the ritual is considered incomplete.

Moreover, in Lai Haraoba, one of the oft-repeated gestures describe the union of divinities Lainingthou and Lairembi; here the male principle Lainingthou is represented by right hand, the female principle Lairembi by the left hand. When both hands turn, it symbolises union and a process of cosmic creation. These hand gestures are initiated by the Amaibis and imitated by each ritual participant – men, women, children – as they continue to offer prayers to the lai-s.

It is also observed that some hand gestures were taken from ordinary, everyday work – however the meaning changes with lyrics and context. For example, champra okpi (picking of lemon) may have originally come from an agrarian past, in dance it can have concrete meaning such as beauty, body, surrounding, or abstract or no meaning. The gesture of champra khaibi (slicing of lemon) is commonly seen in Nata Sankirtana; this hand gesture is adapted in achouba bhangi pareng in Raaslila to signify an offering of prayer. Khujeng leibi(making flowers with both hands in a pattern of 8 may have been derived from movements made with two swords – however in Manipuri dance it is identified as a gesture of obeisance or flower. It is frequently observed, hand gestures convey meaning when not in its static form but as they flow into one movement from the other. The meaning conveyed by the hand also changes with its placement along the body and in space surrounding the body.

Double-handed Gestures

Hand Gestures in Huyen Langlon:

Manipur was at first home to seven warring clans. In medieval times, the kingdom of Manipur has been at war with Ava (Myanmar) for several years before the British interceded – the three parties signed the Treaty of Yandabo (1826) yet internal skirmishes and struggle for power continued to embitter the tripartite relationship. In 1891, British and Manipur were at war, following which the British allowed Manipur to retain its social and cultural autonomy. However, they banned practice of martial arts and the possession of spear and swords – these were not only important for the protection and defense of the people, but for ritualistic purposes too. The art of warfare or Huyen Langlon retreated to small enclaves and could not be observed publicly. More importantly, Huyen Langlon was reminiscent of a martial race, codes of valour, spirituality and morality, and techniques of hunting and smelting, The tradition is also associated with ritual displays of martial techniques in Kwak Tanba festival in the autumn season and propitiation rites such as Lai Haraoba – all of which had to be abandoned or performed in secrecy. In the 1950s, Thang ta or the art of using sword (thang) and spear (ta) was revived, and since then it has been incorporated as a genre of movement within Manipuri, and a stand-alone form. Dances from khousarol (art of spear), thangkairol (art of swordplay), and thengou (patterns for geomancy and auspicious events). Thengou is a movement-based act of summoning spirits – a knowledge system passed to chosen few.

The decorative swordplay is called leiteng thang and freestyle combative swordplay is yanna thang. Unarmed combat is called sarit sarat. In the absence of the weapons and shield, the khutthek of kokchi and laibak are used to signify them. In choreographies, movements and hand gestures from leiteng thang and sarit sarat are often used to display emotions ranging from aggression to tranquillity, forces of nature to abstraction. The mastery of Thang ta movements and hand gestures help a performer build agility, endurance and poise, and limb and body coordination.

Thang Ta Gestures

The sources of indigenous Meitei knowledge and philosophy was collated by an institution of learning called ‘Luwang Nonghumsang’, that came to be known as Pandit Loishang (Council of the Scholars) in the 18th century. It received patronage from the monarchs of Manipur. Puya or manuscripts mentioning dances of divinities were studied alongside the traditions that were sung or kinaesthetically transmitted. These came to describe the gestures and movements of dancers. Individual authors of these traditions were not named, as movement was a product of, by, and for the collective. Many of the translations and texts have been consulted for dance and gestures and made available only in the 20th century; assembling medieval manuscripts written in the archaic vernacular and annotating them in Meiteilon and English have provided for in-depth studying of hand gestures, amongst other features of dances of the Meiteis.

Many of these gestures from Lai Haraoba along with those seen in Vaishnavite dances have been consolidated and codified by Lai Haraoba guru Hidangmayum Thambal Sharma in Jagoi-Khut-thek (1980) as these were only transmitted orally or through observation. He named them in Meitei language. These gestures follow the narratives that is danced by Maibis in the Lai Haraoba. These gestures are codified for technical precision, therefore the processes in which they are learnt and memorised are different from how they are learnt by the Maibis. The single-handed and two-handed gestures as codified and named in H. Thambal Sharma’s book accompanies this article.

Hand gestures therefore have multiple names. H. Thambal Sharma’s Naap Khutthek is most popularly recognised as champra okpi – or gesture of lemon-picking. Dancers from other Indian tradition s will recognise it as a restrained form of alapallava. Similarly the gesture known as hamsasya in Abhinaya Darpan, is sometimes identified as lasing kappi khutthek; in scholar Surchand Sharma’s compendium Meitei Jagoi, it is identified as samdansya and, in H. Thambal Sharma’s book it is midway between mit and mitchi khutthek.

Writings of Khumallambam Yaima (Meitei Jagoi : Anoirol, 1973/1981), Moirangthem Chandra ed. (Panthoibi Khongulon, 1963), Pandit Ngariyanbam Kulachandra (Meetei Lai-Haraoba , 1963), Kumar Maibi (Kanglei Umanglai Haraoba,1988),Wahengbam Lukhoi (Lai Haraoba,1989) and Ningthoukhongjam Khelchadra (Manipuri Thang ta, 1971) – provide detailed understanding of structures of dance in ritual of Lai Haraoba. Indigenous dance aesthetics has been further studied in depth by Saroj Nalini Arambam Parratt (with John Parratt; Pleasing of the Gods: Meitei Lai Haraoba, 1997), N. Vijaylakshmi Brara (Politics, Society and Cosmology in India’s North-East, 1998) and Manjusri Chaki Sircar (Feminism in a Traditional Society-Women of the Manipur Valley, 1984). These texts will lay out the history and context of dances of Manipur alongside an introduction to the lexicon.

Watch this space for more blogposts in our #WednesdayWisdom series on hasta.