Aharyabhinaya in Odissi

By Pallavi Basak Vijay

#WednesdayWisdom is a series that began during the 40th anniversary celebration of Akademi to revisit Indian classical dance roots by sharing gems of knowledge from ancient Shastras (dance texts) that hold relevance even today. The blog is curated by Bharatanatyam artist, Suhani Dhanki, along with with our Head of Marketing, Antareepa Thakur.

In this blog series, we are inviting artists practicing different South Asian dance styles to contribute some interesting facts about their art forms, some of them rarely seen in the UK. Read our previous blogs in this series here.

This blog post on Aharyabhinaya in Odissi is compiled by Pallavi Basak Vijay, an Odissi dancer and teacher where she describes the ornamentation, hair-style and costumes used in Odissi, a South Asian dance style originating from Orissa, a state in the eastern part of India. The beautiful illustrations are by Vanessa Cavron.

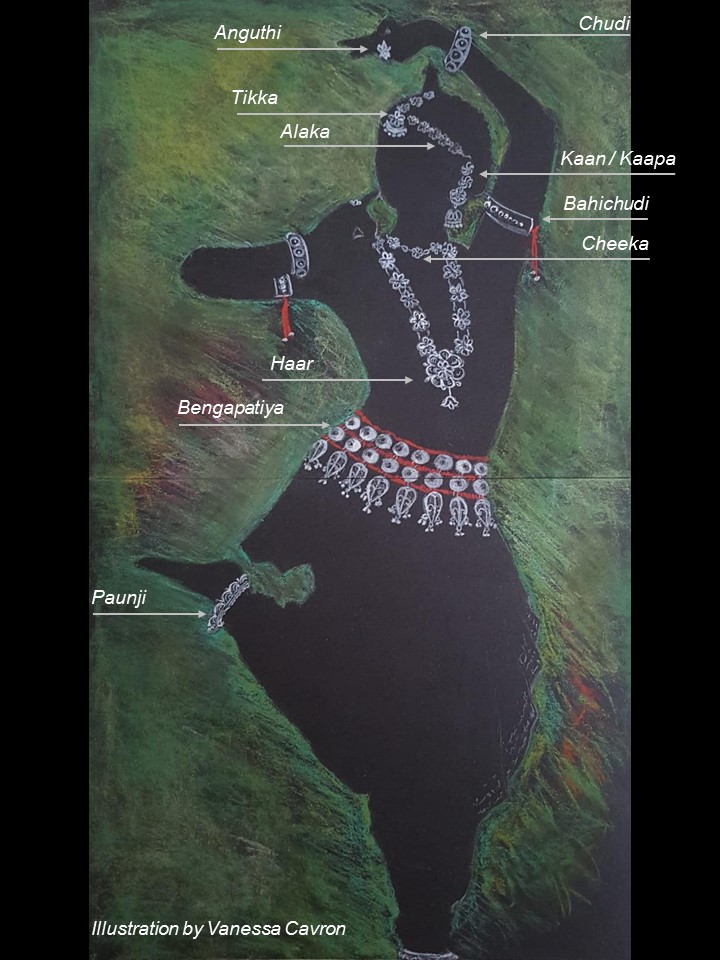

Odissi Jewellery (Alankara)

The Indian classical dance form of Odissi dance is unique among other classical traditions of India in its use of silver ornaments. The artists only wear intricate filigree silver or white jewellery pieces; filigree, meaning thin wire in French, is called Tarchasi in Oriya.

Making of Silver/Filigree Ornaments

Over 500 years old, this art form is traditionally done by highly skilled local artisans on the shores of Orissa in Eastern India. Creating each piece is a collaboration between several artisans, each specialising in one of the many steps that turn a piece of raw silver into a handcrafted work of art. First, silver is melted in a small clay pot that is put into a bucket full of hot coal. The temperature is regulated through a bellow that is hand operated by a crank. The melting process takes about ten minutes after which the silver is poured into a small, rod-like mould and cooled by submerging the rod in water. The rod is then placed into a machine that will press the rod into a long, thin wire. This tedious and physically demanding process has been done traditionally by hand and takes two men to turn the crank.

This malleable wire can either be hand carved immediately with intricate designs, or smouldered over a small kerosene fire with one artisan directing the flame with a hollow tube held in his mouth while the other moulds the wire into the desired frame. The wires are then strung together, twisted and shaped into a design by the artist’s precise fingers. Soldering is done by placing the piece into a mixture of borax powder and water, sprinkling soldering powder onto it and then placing it once again under the small flame. This insures that the detail of the design will stay intact. Once this is done, the artist will then take the warm piece and shape it into its form as an ornament. Finally, the ornament is filed down and polished by soaking it in a frothy mixture of water and split nuts from a tree called “soap nut.” The ornament is now ready to be worn by the dancer.

Ornaments

1. The female dance artist wears a single silver Tikka or sinthi along the parting of her hair.

2. A silver tikka is also worn by female artist along with decorative silver chains that extend from forehead to ears. This ornament together is known as Alaka or Mathapatti.

3. Kaan or Kaapa are earrings that cover the entire ear. They are in the shape of a peacock or other geometric designs and sometimes are accompanied by large dangling bell shaped jhumkas attached at the bottom of the piece.

4. Both male and female dancers may wear two to four necklaces:

a. Cheeka – a smaller one worn close to the neck.

b. Haara – a longer necklace with a hanging pendant.

5. Dancers wear a three-tiered silver belt, Bengapatiya, around their waist. It is usually made with secular silver disks strung together in three rows. This is also worn by both male and female artists.

6. The artists may also wear silver armbands or Taaita or Baajuband or Bahichudi.

7. The wide filigreed bangles are known as Chud or Chudi or Kankana.

8. Female artists often wear a large silver filigree pin or a crescent of silver wreath over the central pin on their hair bun.

9. The anklets are called Paunji.

10. The artist may also wear rings or Anguthi on their fingers.

Odissi Hair-styling (Kesh-Sajja)

Abhinaya Chandrika, a dance text by Maheshvara Mahapatra, contains elaborate hair designs to be worn by a female Odissi dancer. Some of these are also seen in the temple sculptures of Orissa, a state in Eastern India.

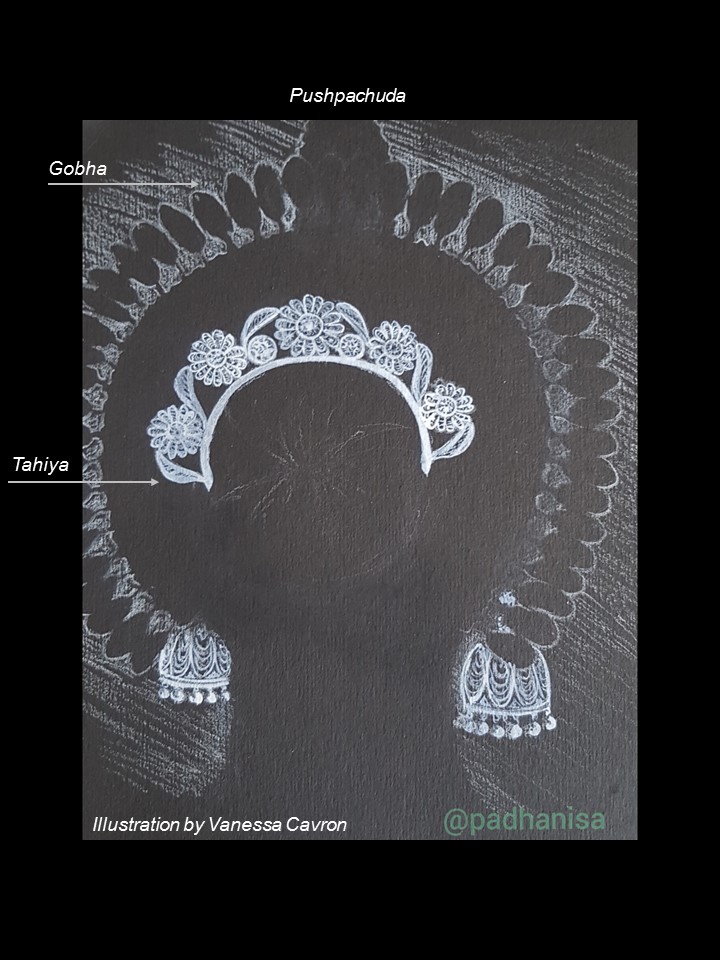

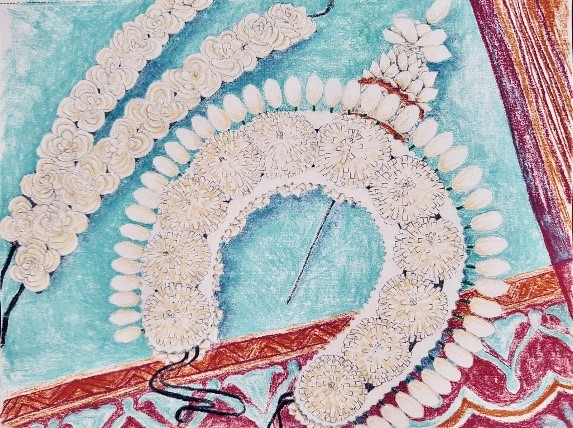

The most commonly worn style is a hair bun at the back of the head adorned with a pushpuchuda (a head gear). Tying the hair at the back of the head, and around a large ring to give fullness to the shape creates this beautiful hairstyle. This is occasionally combined with hair braided down the back, if the dancer chooses to follow the Mahari tradition.

Pushpachuda is made of Shola pith, a plant-based material best known for making the British Colonial pattern pith helmets. Moulding the soft, white, inner stalk of the shola pith, which grows across Odisha and Bengal, is a unique regional craft. Although organic, its texture is quite similar to the plastic Styrofoam or thermocol. The art of carving shola pith has been used to create the extraordinary and distinct flowers in the elaborate hairdo of an Odissi dancer.

The Pushpachuda (also known as Mukoot) consists of two parts:

Gobha – Flower decorated back-piece called Gobha sits around the dancers hair pulled into a bun at the back of the head. The flowers are designed in the shape of Jasmine, Champa (one of the five flowers of Lord Krishna’s arrows) and Kadamba (the flowers of the tree under which Radha would wait for her beloved Lord Krishna).

Tahiya – The longer piece that emerges from the centre of Gobha is called Tahiya, and this represents the spire of the iconic Jagannath temple in Odisha or the flute of Lord Krishna.

Odissi Costume (Beshbhusha)

History of the costume

Maharis, who danced in the temple, typically wore black velvet bodices with the sari wrapped from the waist down. When Odissi began to be presented upon the stage, the sari was first wrapped as a dhoti to form a divided ‘pyjama’, with the decorative design end of the sari, or pallu, spread in front.

Over the years, various styles of tailoring the sari into the costume were developed.

Styles of tailoring

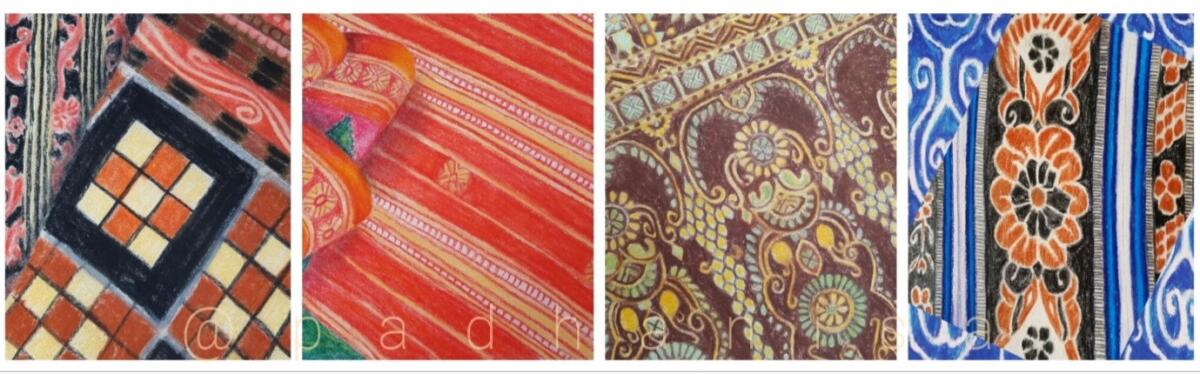

Late Odissi Guru Kelucharan Mohapatra designed a tailored costume. In this design, the decorative end of the sari or pallu is pleated and snapped on to the costume so that it fans out as the dancer sits in the chauka position, This pattern came to be known as the fan style costume.

In this costume design, the blouse is made from the same sari material as the cloth draping the front of the dancer.

A popular variation on the costume design is to have the decorative front pleated in a vertical fashion down the front that is closer to the Mahari temple dancer tradition. Various artists have incorporated several variations on the length or angle of the front fan in the design, but the main distinction is the vertically draped front or the knee-to-knee fanned out cloth also known as the dhoti style or Mahari style costume.

Parts of the costume

- A fabric is fastened around the hips from behind which define the hipline, known as the natabari.

- The blouse (made from the same sari material as is the cloth draping the front of the dancer)

- Aanchal or the Pallu (also from the same sari material) is pleated as is the cloth draping the front of the dancer, that covers the chest. This is mainly worn by the female dancers.

Side-fan/dhoti style

Middle-fan style costume

Material

The woven sari used for a costume can be from any of the many wonderful traditions of the state, in particular those from Sambalpur, Berhampur and Cuttack. While the resplendent Sambhalpur silk ikkats are known for their intricate weaving technique and subtle colour combinations, the Cuttack colours are more contrasting. The Berhampur silks are known for their narrow rudraksha borders and stunning combinations. Another style that found favour with many dancers was the Bomkai sarees with their long and delicately woven pallus, which could easily be converted into the fan in the front. The fabric used for costumes on stage is mostly pure silk, though in some cases dancers do opt for baafta, a mixture of cotton and silk pure cotton as well.

Credit: drawings by Vanessa Cavron; header image courtesy of Pallavi Basak Vijay

Watch this space for more blogposts in our #WednesdayWisdom series.