Hasta in Manipuri – Part 2

#WednesdayWisdom is a series that began during the 40th anniversary celebration of Akademi to revisit Indian classical dance roots by sharing gems of knowledge from ancient Shastras (dance texts) that hold relevance even today. The blog is curated by Bharatanatyam artist, Suhani Dhanki, along with with our Head of Marketing, Antareepa Thakur.

In this blog series, we are inviting artists practicing different South Asian dance styles to contribute some interesting facts about their art forms, some of them rarely seen in the UK. Read our previous blogs in this series here.

This blogpost on Hasta in Manipuri is researched and written by Debanjali Biswas, a scholar of social anthropology and performance studies and the co-director of performance collaborative – Mitradheya. She is a Manipuri dancer trained in the style of Oja Bipin Singh and is based in London.

Designed by Apollonia Bauer.

In response to last week’s blog post, I was reminded by a Meitei scholar that the tradition that I call Huyen Lanlong is more commonly referred to as Huyen Lalong in Manipur. His comment is important for two reasons; firstly, subtexts of vernacular words often get lost in linguistic assimilation and translation, especially amidst culturally plural community like the Meiteis. Secondly, scholars and practitioners often spell differently in English to distinguish their contributions during the formal documentation of their practices. Readers may come across – Huyyen Lalong/Huyen Llalong/Huyen Landon for the same tradition. Similarly, Lai Haraoba is sometimes spelt Lai Harouba, Nata Sankirtana is Natsankirtan, Raas Lila is Ras Leela. These suggest a complex interplay of text and oral traditions, pedagogy and spontaneity, poetics and politics within a practice. Cultural Historian Kapila Vatsayan once wrote ‘Manipuri may be described as a dance form which is at once the oldest and the youngest among the classical dances’ to denote the ever changing structures of Manipuri dance (1992). Vatsayan also noted, that the easy flow of movements should not be mistaken for simplicity; this statement is significant for the way we as an audience view Manipuri dance.

In this segment, I will introduce khutthek as derived from Nata Sankirtana and Raas Lila rituals – these are Vaishnavite Hindu traditions.

Krishna lifting Giri Govardhana

Krishna subjugating the serpent Kaaliya

Krishna, the deer-eyed one

Brief History of the Traditions

The Lai Haraoba and Huyen Langlon traditions that I discussed in the last blog post can broadly be identified as pre-Vaishnavite way of life. Alongside these, the presence of Gaudiya Vaishnavism in Manipur from late 18th c. was instrumental in bringing changes to Meitei socio-religious life. Nata Sankirtana and Raas Lila were introduced as congregational form of worship for Vaishnavite deities. These are sung and danced in spaces marked sacred by the believers. As forms of worship, they are integral to the expression of devotion and dissemination of Krishna’s naam i.e. rhythmic repetition of several appellations given to the deity Krishna.

The sacred space is generally a mandop or a four-sided pillared hall that is located within the premises of a household, a Hindu temple or a locality. Prior to the rituals, these spaces are sanctified and generously decorated to resemble Krishna’s cosmic abode as it is believed Krishna himself descends and dances in the raas-mandop. The other site where Nata Sankirtana and Raas Lila is performed, is of course, the stage. Dances and movements are derived from these traditions for stage performances are much shorter in duration, shed of complex rituals and prayers. However, in essence, the performers must prepare themselves as if they are stepping into the raasmandop as Krishna and Radha, and dressed as Gopis – Krishna’s devotees and consorts in Raas. According to local history, the dances of Raas Lila were dreamt by King Chingthangkhomba (1748 – 1798) , also known as Maharaja Bhagyachandra.

Amidst great political upheaval, Chingthangkhomba dreamt Krishna asking him to set up his idol in a temple and create devotional forms in lieu of aiding him with power and spiritual strength. Soon after, the king housed the idol of Govindaji (Lord Krishna) in a temple. The present-day temple is in Imphal, Manipur’s Capital City, where music and dance continue to be performed in the praise of Krishna. In his dream, the king was told by Krishna to emulate His garments, His movements, and His gestures which were later described and taught to the many artist guilds. In 1777, on an autumnal full-moon night, the first Maharaas Lila was observed under the king’s guidance. His daughter Sija Lai Oibi Bimbavati danced as Krishna’s prime consort. She, along with her father, became great devotees of Govindaji and subsequently created the basic tenets of devotional dance and music in Raas Lila.

Besides Chingthangkhomba’s dream and other mythic beginnings of the Raas Lila, the Meiteis wholeheartedly believe that Krishna descends to dance in the Raas. On the other hand, the rational attitude that Raas has evolved out of an older ritual – Lai Haraoba, and was composed by Amaibi, Amaiba, Penakhomba of the older faith alosngside instructors well-versed in the Śrīmad Bhāgavata Mahā Purāṇa and Assam and Bengal’s kirtana tradition – is also accepted. The structure of Raas Lila was thus decided by kings, composers (oja), scholars (maichou), devotees, and guilds/councils called loishang.

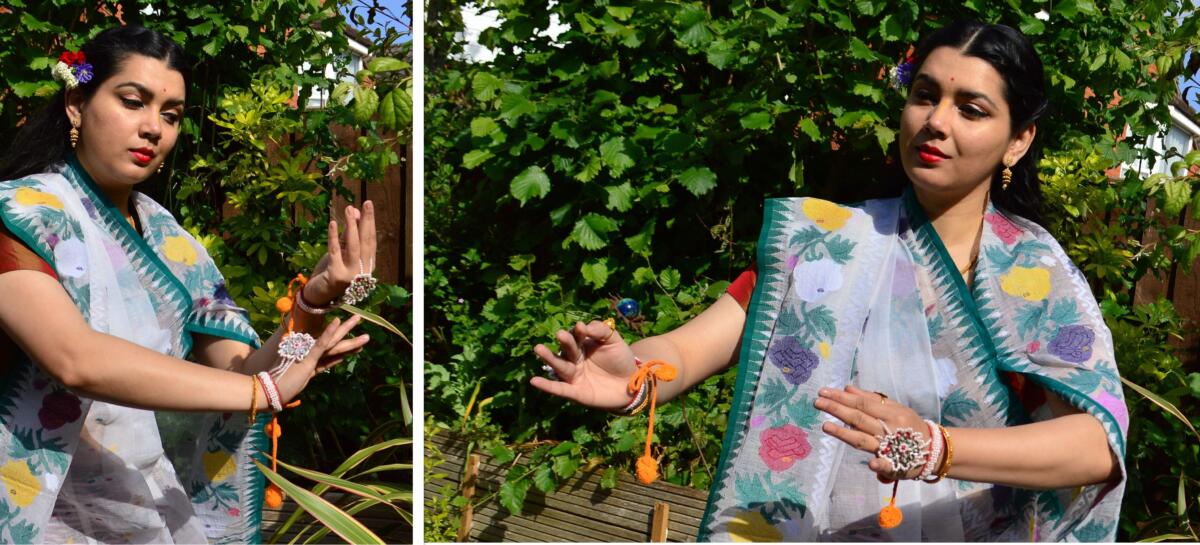

Hand Gestures Depicting Krishna

Hand Gestures in Raas Lila

As devotees and participants would come in large numbers to attend the rituals, movements and gestures of the dances had to be simple. Moreover Raas Lila expresses ideals of restraint and modesty through artistry. The economy of facial and gestural expressions in Raas Lila is ingrained in several factors, such as, Vaishnav ideas of devotional service, local traditions of movements created by observing the nature, and kinetic transmission of dance as knowledge. Hand gestures convey suggestive, hidden meanings of the sung texts. Raas Lila is replete with repetitive hand gestures that not only symbolically indicate a union between Krishna and his consorts, but also a spiritual connection between Krishna and his devotees.

Hand Gestures Depicting Gopis and Radha

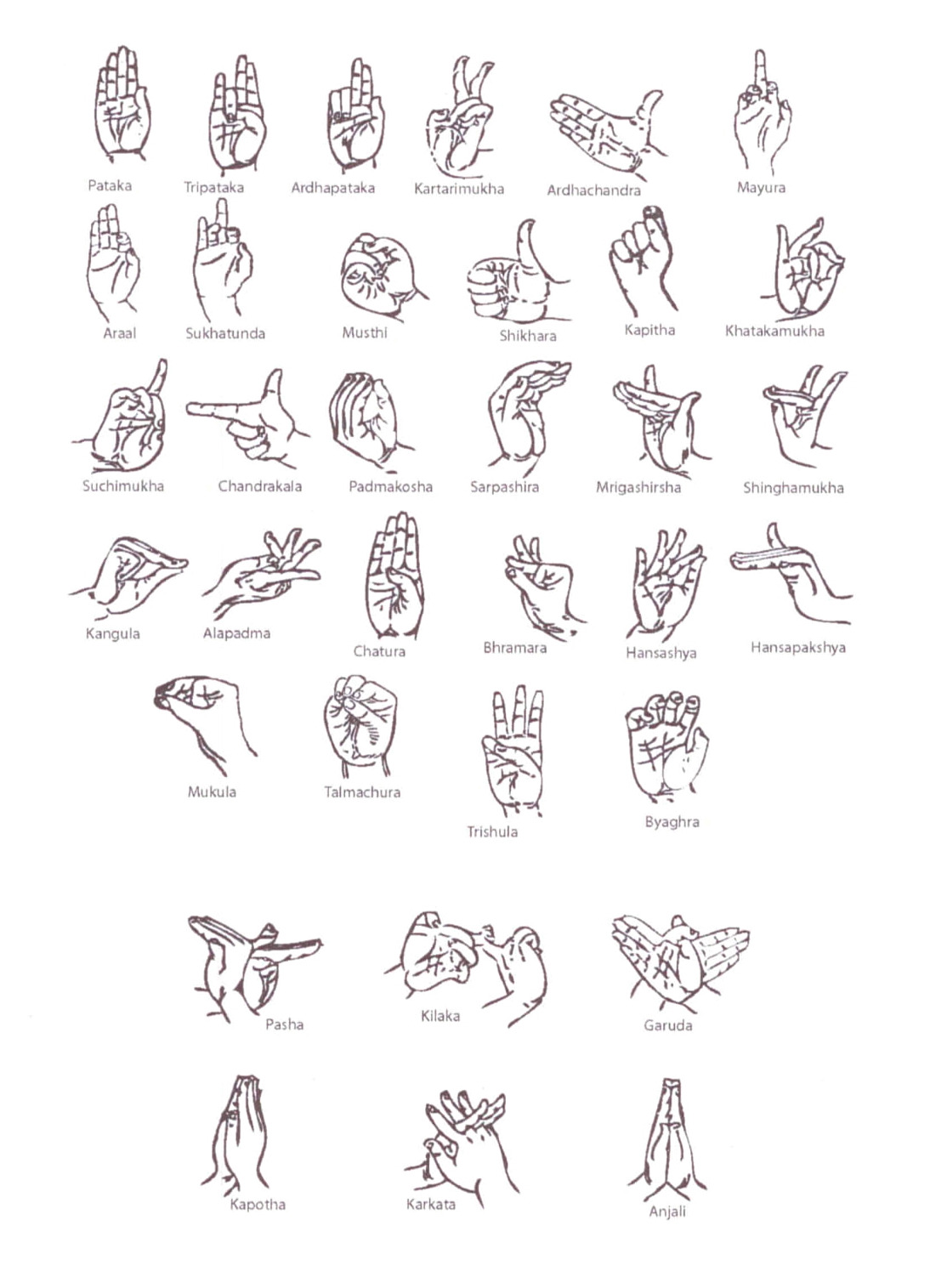

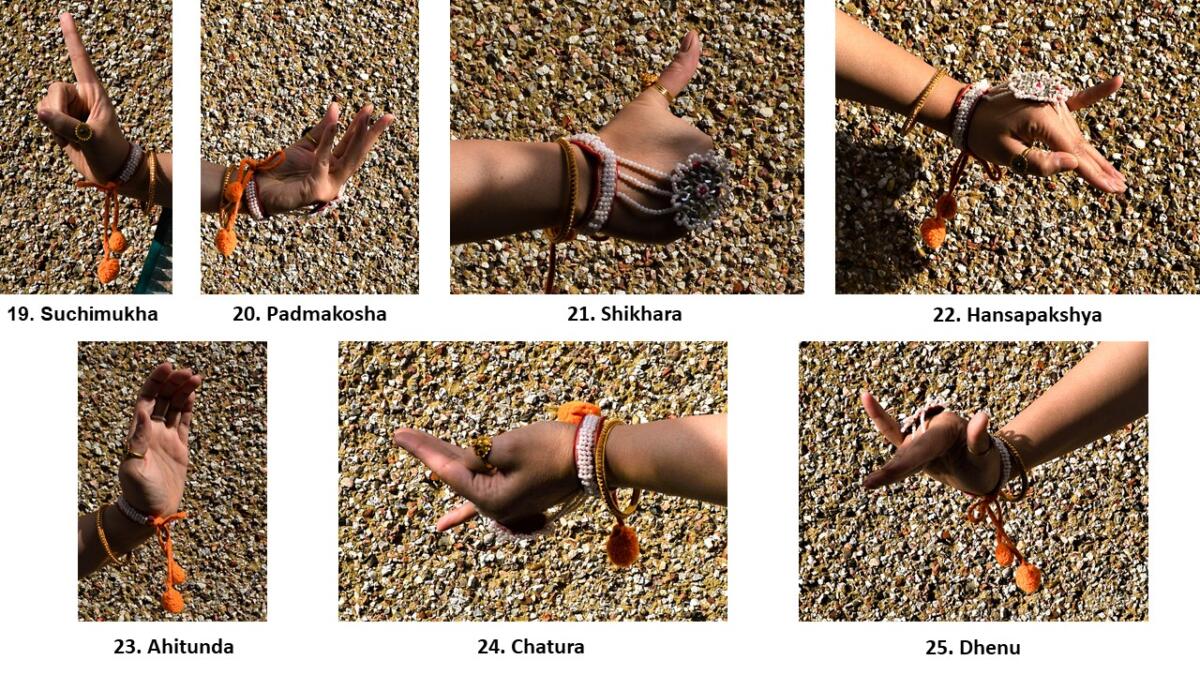

Khut thek taught in most Manipuri institutions are vividly outlined in Oja Maisnam Amubi Singh’s manual on dance – Chali (1964). Titled as nartan hasta, he discusses the Asamyukta and Samyukta mudras as explained in Nandikeshwara’s Abhinaya Darpanam. He adds a few from his practice – Shri Vishnugi Avatar tara (ten incarnations of Vishnu), jati khangnaba khut (strata of society), bandhav hasta (familial bonds), graha mapan gi khutthek (nine planets), laishinggi matot takpa mudra (gestures indicating various divinities). The mudras from Abhinaya Darpanam are taught in Jawaharlal Nehru Manipuri Dance Academy – an affiliate of Sangeet Natak Akademi, New Delhi.

Hand Gestures as taught in JNMDA following Abhinaya Darpan and

Guru Maisnam Amubi Singh’s Nartan Hasta (1965)

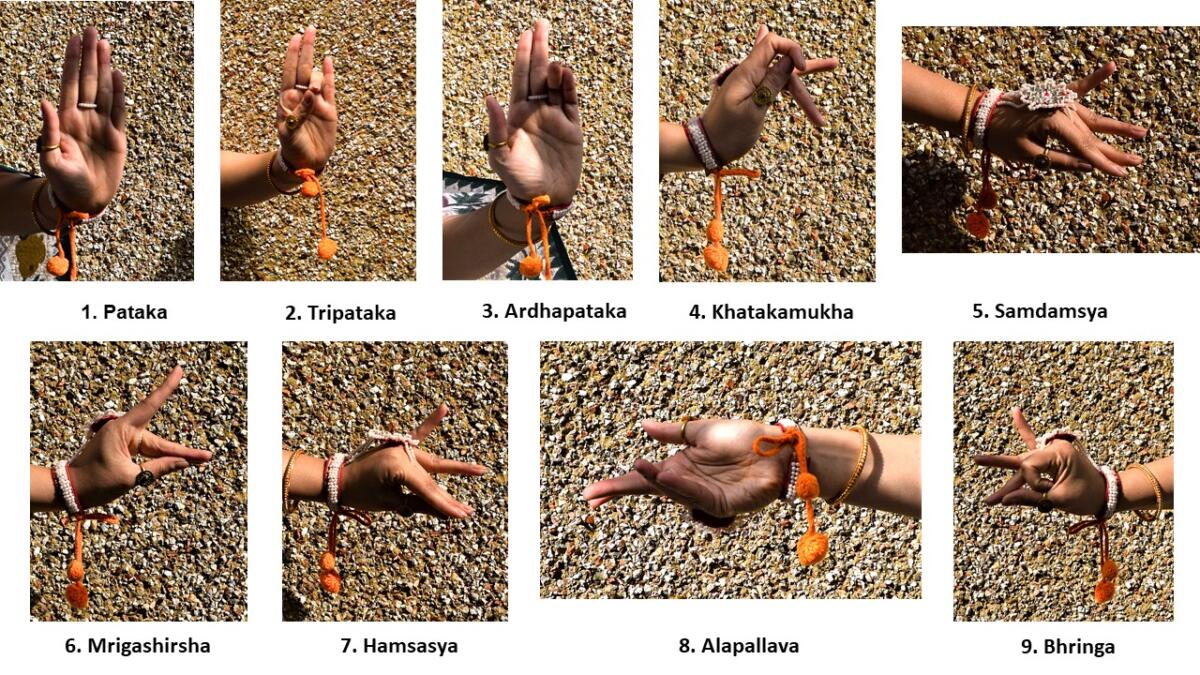

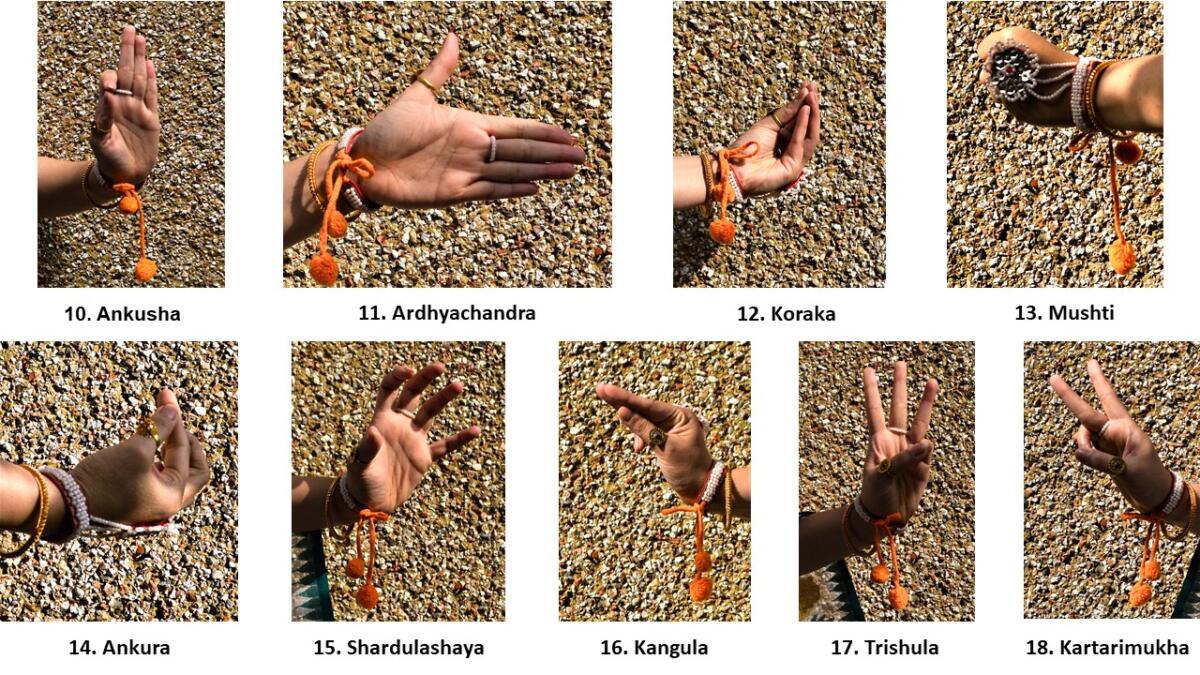

My training in the style of Oja Bipin Singh had me learn the khutthek as outlined in scholar Surchand Sharma’s Meitei Jagoi: II (1965). The 25 Asamyukta and 12 Samyukta khutthek are shown in images ahead. The most used Asamyukta khutthek are Pataka and Samdamsya- these stand in for concrete meanings and abstract gestures and many dances combine Pataka and Samdamsya to create entire movement sections or pareng.

Asamyukta Khutthek

Usage Examples of Khatakamukha

Showing Ananga’s bow

Showing Krishna shining like Marakata

In the basic position, the two hands in samdamsya khutthek pointing outwards remain on two sides of the body making an imaginary slight curvilinear triangle. The basic movement of Chali on an eight-beat cycle consists of a series of gestures where fingers of both hands close and open simultaneously first facing away from the ground, then facing towards the ground (this can be compared to “Karana’s of Dance-hands” i.e. Āveṣṭita, Udveṣṭita, Vyavarita and Parivartita. in Chapter IX of Nāṭyaśāstra).

Basic Position in Manipuri

The Samyukta khutthek contain meaning by themselves – shankha-chakra are weapons of Vishnu, rambhasuma-pushpaputa are gestures of holding flowers, kokila-shuka are birds and so on.

Samyukta Khutthek

The khutthek as seen in important segments such as Bhangi Pareng in Raas Lila have not been codified but they are briefly mentioned in H. Thambal Sharma, Surchand Sharma and M. Amubi Singh’s compendiums. In Bhangi Pareng, one-handed and two-handed gestures are repeated as flowers strung in a garland. These gestures are suggestive of the union of divine and mortal in the ritual; however gestures and movements from Bhangi Pareng Achouba, Khurumba Pareng, Gopi Vrindavan Pareng, Gostha Vrindavan Pareng and Gostha Bhangi Pareng are regularly used in nrtta or pure dance. Narratives on abhinaya and sung-texts sometimes provide the basis of combining Asamyukta khutthek together.

Combinations of Asamyukta Khutthek

Book or Letter

Bee on a Flower

Ganges Flowing out of Shiva’s Locks

Most dances are based on Krishna’s consummate love-plays in the celestial forest of Vrindavan. The hand gestures follow the sung poetry to describe intricate details of how Krishna is attired, His gait and gestures, His speech and His prowess in dance, flute-play, tact and strength in battling evil characters. Hand gestures are also used to describe Krishna’s consort and their trysts, how they dress themselves or are dressed by their chaperones, how they feel and speak to each other in separation and in union, the flora and fauna in full glory.

Showing Long Tresses

Stringing a Garland

In Praise of the Beauty of Divinities

In these dances, performers wear multiple ornaments on tehir arms, the most prominent is Khuttam topi on the hands. It is highly uncommon to accentuate their hands with red dye.

Hand gestures in Nata Sankirtana

The rulers of medieval Manipur were familiar with some Hindu performance and religious traditions, one of which was known as Bangadesh Pala (old style of Kirtan singing in Bengal style). After the introduction of Gaudiya Vaishnavism in the kingdom, new performance styles came to be incorporated with old traditions; this gave rise to Nata Sankirtana, also known as Anouba Pala. Here , Nata means the ‘dancer’ or ‘what is enacted’. The entire Tāla system i.e. the rhythmic arrangement of beats in patterns and cycles in Manipuri dance is derived from Nata Sankirtana.

Nata Sankirtana artistes describe the 15th century saint Caitanya’s emotions of being a spiritual witness to Krishna and Radha’s play. The saint is imagined to have embodied erotic mood of both divinities. The sankirtana performers sing to Krishna-Radha, Caitanya, and the audience tying them together by the invisible thread of bhakti and summoning them.

Hand Gestures of Devotion

Summoning the Divine

Bowing in Reverence

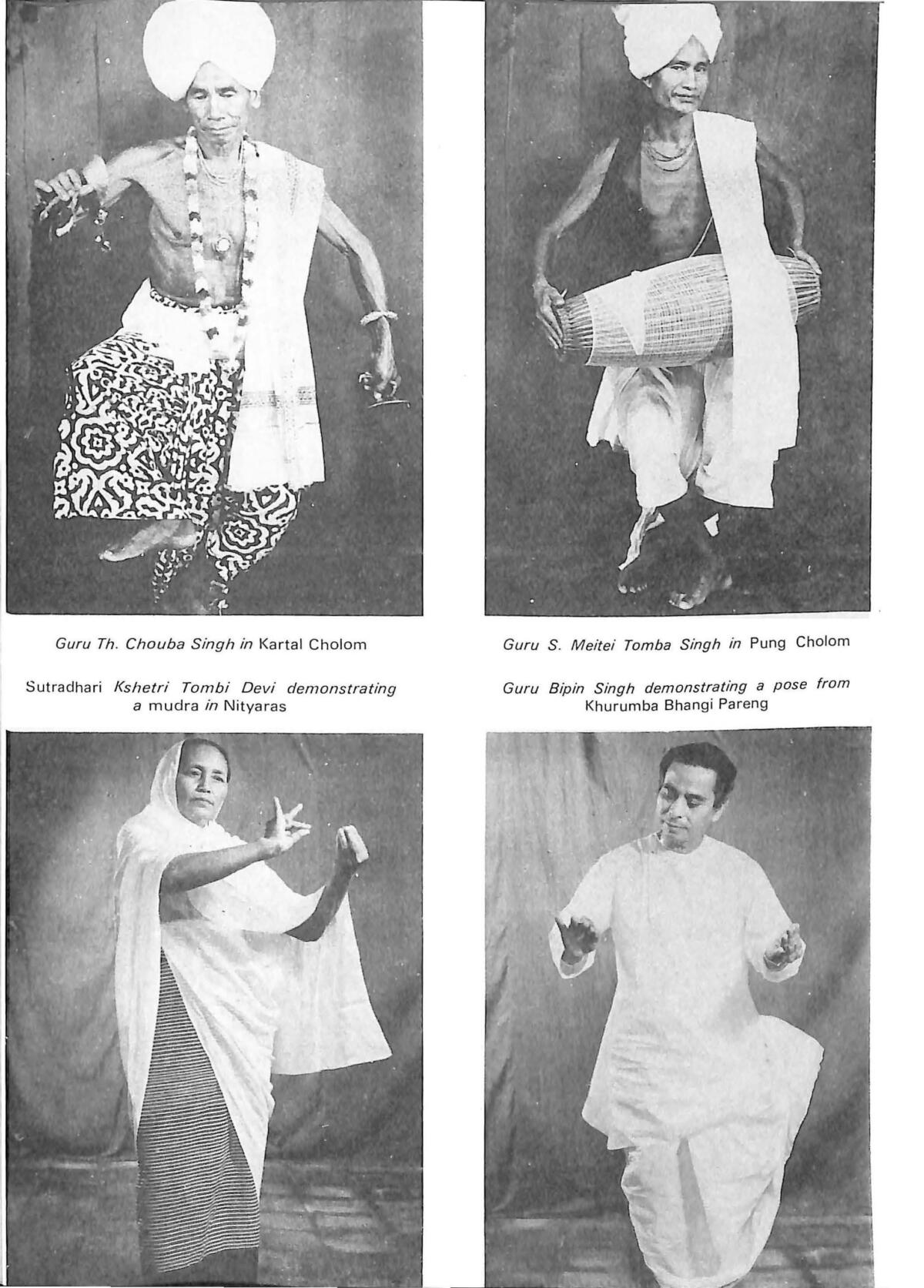

After the completion of raag achouba (percussion vocabulary), gourachandrika (invocation of Caitanya), Krishna roop (description of divinity from toe to head), eshei raga taba (infusion of life into the idol) – spectator-devotees bow to signify the presence of Krishna. Each of these segments are sung with elaborate hand gestures, and musical instruments such as kartaal (large cymbal), pung (percussive instrument) punctuated by moibung (conch shell). Nata Sankirtana is performed for the Astakal (eight services) at Vaishnav shrines as well as alongside each Hindu rite-of-passage. When songs are performed only by men, it is a nupa pala. Nupi Pala is performed by women. The singing is accompanied by pung-yeiba or men who play the pung (percussion) and manjira (small cymbals). The pung-yeiba dance in the centre – during interludes, they would burst into acrobatic movements, walking in various patterns on the ground, vigorously playing the instruments and gesticulating at the same time. These movements are called pung cholom and kartaal cholom.

Gestures in Manipuri NCPA Quarterly (3/1974)

Although Nata Sankirtana artists hold or play the instruments when they perform, few movements and hand gestures have been derived from them. Holding the pung, manjira or kartaal with both hands, marking the beats of rhythm with a flick of wrist – are commonly seen in tandava or the male style. In Oja Bipin Singh’s choreographies such as Tanum, Mridu Uddhata Krishna Nartan, Brahmataal Nartan – the vigorous Nata Sankirtana style has been combined with gentler Raas Lila dances. Nata Sankirtana gestures and mudras depicting Dasavatar are also common in seasonal dances such as Khubak Ishei (dances with claps during Ratha Yatra festival) and Holi Pala.

Sankirtana Gestures

The Vaishnavite traditions are based on the philosophy of Rasa-pancadhyayi or ‘The Five Chapters on the Rasa’ within the Śrīmad Bhāgavata Mahā Purāṇa. Texts such as Ujjalanilamani of Rupa Goswami (b.1489) and Caitanya Caritamrita of Krishnadasa Kaviraja’s (b. 1518) deepened the discourses and expression on bhakti. Kapila Vatsayan’s Indian Classical Dance (1992), Sarayu Doshi’s Dances of Manipur: The Classical Tradition (1989), Rasa Humphumari published by Manipur State Kala Akademi (1978), Elangbam Nilakanta Singh’s Manipuri Sankirtana(1978), Nogthombam Premchand’s Rituals and Performances (2005) – offer a comprehensive view of dances of Manipur and the four ritual traditions that I have discussed in the blog posts.

Watch this space for more blogposts in our #WednesdayWisdom series on hasta.