Ethnic? Exotic? The language of Indian classical dances in the UK

This year, we have embarked on an enormous archiving adventure to celebrate Akademi’s heritage and preserve our history at the V&A Museum. We have some wonderful volunteers who are helping us in this process. We invited them to share their experience, work and findings on South Asian dance in the UK. This first blog post in the series deals with critiquing the language commonly used when talking of certain art forms in the UK as is evidenced in Akademi’s archives, and Akademi’s endeavours in making these art forms relatable and accessible over the years.

Subhashini Goda is a Bharatanatyam artiste and a writer from Chennai, India. Experimenting with different forms of movement practices, her creativity is founded on memories of growing up in a multilingual, multicultural neighbourhood layered with simple everyday narratives of literature, rituals, storytelling, and philosophy enhanced by complex global perspectives. With a background in English Literature, she is, at the moment, pursuing her International Erasmus Masters in Dance Anthropology (Choreomundus) and her research inclines towards performative practices from India and the Indian diaspora, ritual transgression, politics, identity, migration and memory.

On a trip to Bratislava, I ended up in a small store called “The Ethnic Shop” that sold varied products from different parts of the non-Western world, predominantly those from the Indian subcontinent. It was here that I bought myself a Mexican Poncho made in Nepal. The irony didn’t escape me. In an era where we are all so multicultural, does the word ethnic bear any significance at all? As I sifted through Akademi’s rich repository of their past saved meticulously as archives – as collages of little paper clippings – my intention was to explore words.

“Cultural Invasion!”

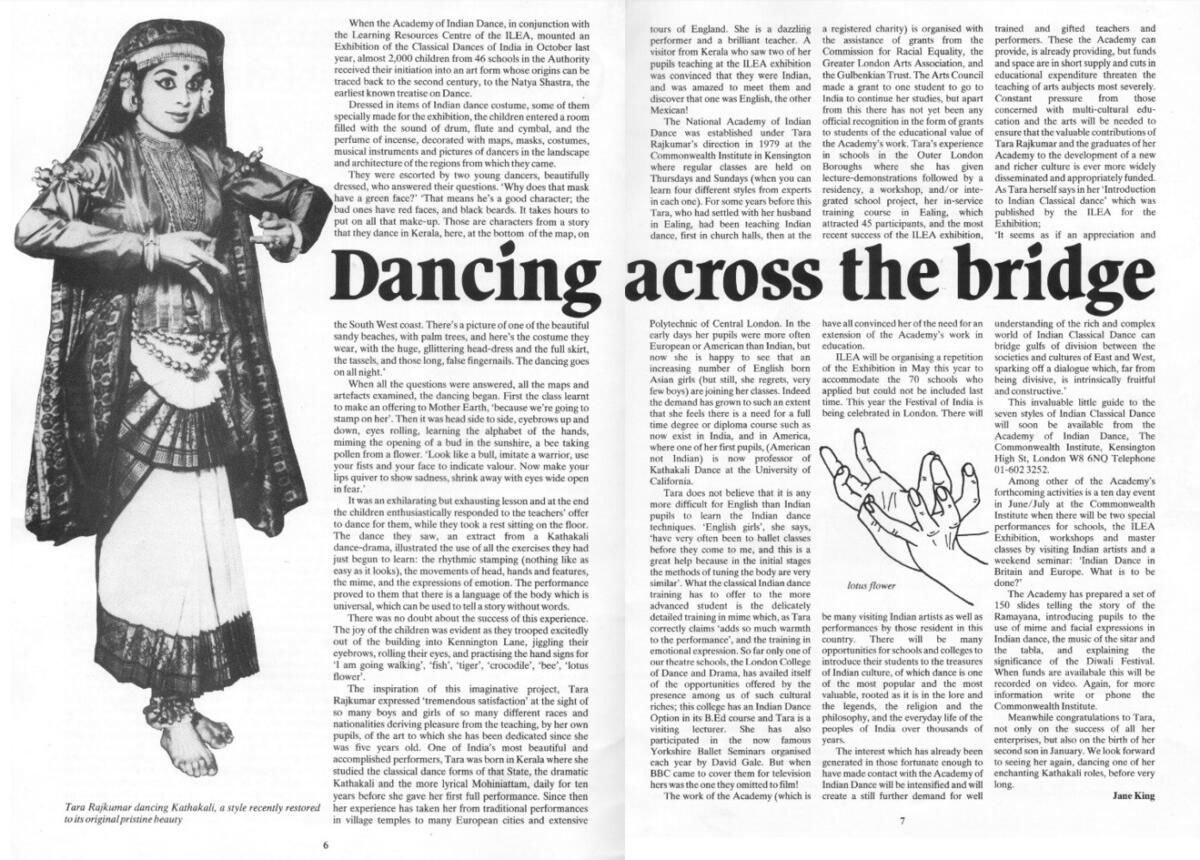

In 1980, Tara Rajkumar exclaims in an article, “anything that smacks of ethnic seems to leave them cold”, referring to opinions on Indian dancing in the UK. Ethnic. Here is a word we come across often in most places. Ethnic arts, ethnic attires, ethnic languages, ethnic minorities. Somehow, ethnic seems to have an implication of all that isn’t from the West. We have truly come a long way – much of these words aren’t used anymore. And yet, in little pockets, these implications are hard to miss.

“It’s only words!” From the 80’s…

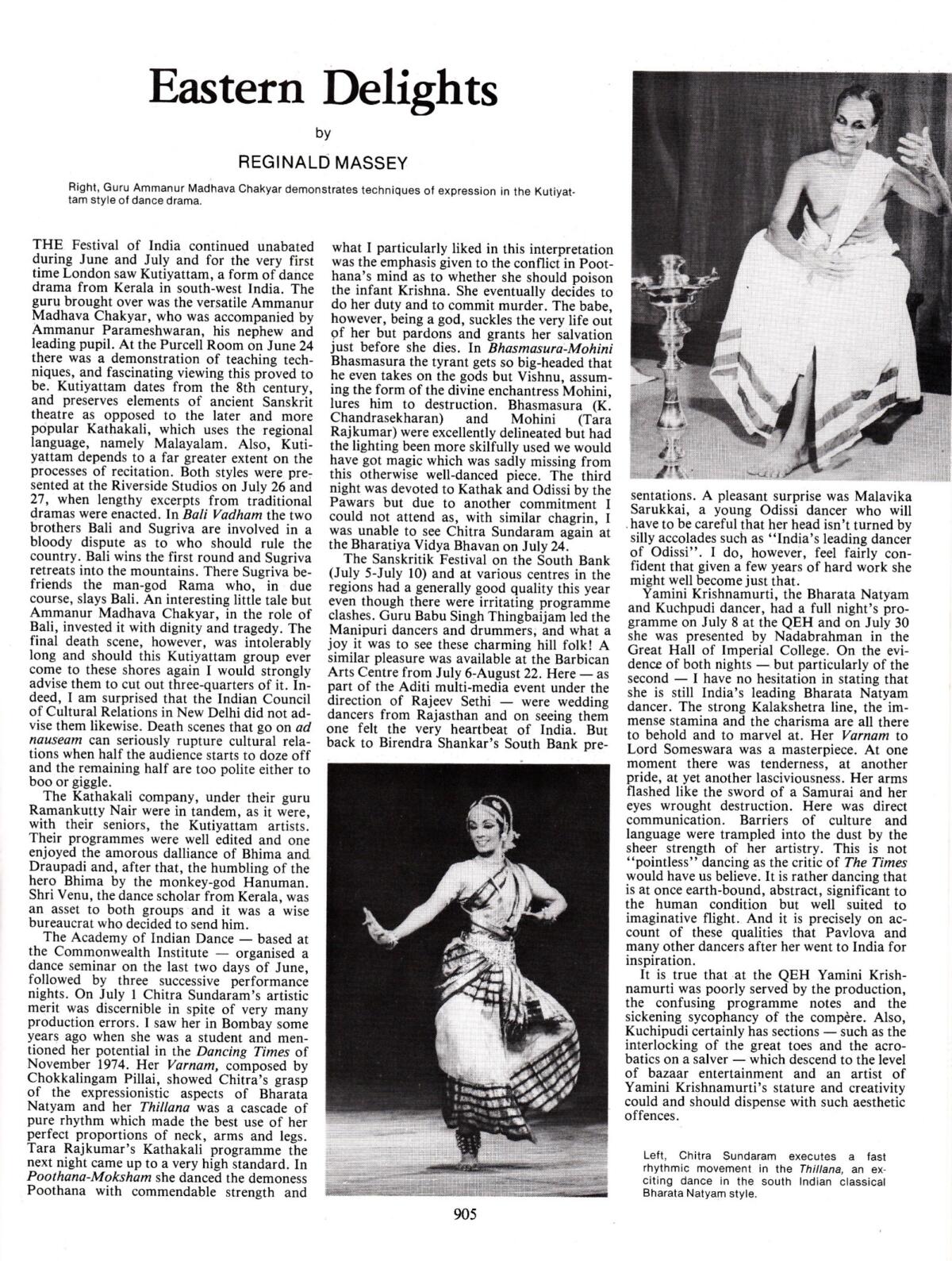

The year is 1982. In a review article called “Eastern Delights”, a reviewer talks on how a death scene from the dance style of Kudiyattam was “intolerably long” and further advises on shortening it if they were to “ever come to these shores again”. While the reviewer’s seeming ignorance of the centuries-old art form is palpable, he further adds that such scenes could “rupture cultural relations” as the audience either doze off or are “too polite to boo or giggle”.

This is significant because it seems that there never is an end to the unforgiving western gaze on the non-western aesthetic and traditions, and the unfamiliarity of such artforms were predominantly expressed in such reviews that, ironically, were the only sources of information on the forms as well.

When Sitara Thobani remarks on how there is a certain way of writing that often accompanies writing on the east, with terms such as “flashing eyes”, “delicious expression” (Thobani, 22: 2017) and so on – the discussion goes back to this dichotomy often made in the gaze of what constitutes the East, and what constitutes the West. There either seems to be absolute criticism, or liberal exoticism with a sprinkling of words such as “marvellous gaze”, “culminating in a shattering climax” and “contrastingly tender and frenzied”. Somewhere, the dance and the dancer are lost in this war of words and translation.

The struggle to fit into a certain “class” of viewership turns real as well. The reviewer, in the same article, states that a dancer of Yamini Krishnamurthy’s stature should not “descend to the level of bazaar” entertainment, and dispense “aesthetic offences”. One is left wondering if an Indian classical dance form can adapt itself to be accepted by spectators from diverse backgrounds? And if it does, how does one navigate the label of “ethnic”, and “exotic”, even if practiced by people born in the UK?

Tania Rose, in an article in 1991, suggests how the inclusion of these art forms into the British Arts scene have come a long way. It required departure from modes of teaching that were native to these dancers from different parts of India, and mould their methodologies, and often, the concert repertoires and themes to a more ‘suitable’ genre. Thus, dance choreographies that departed from religious mythologies and ventured into secular spaces. While it is appreciative, Tania’s article still suggests a bit of a lacking between the “elite dance” and the “dance of the community” in the UK – this contrast mirrors conversation about what constitutes main stream dances, and what ethnic minorities have to offer. How does one bridge the gap between what is elite and what isn’t? And if so, how does one define classicism and elitism? Navigating such spaces have always been a challenge, and continues to be

…To the Now!

“The compartments of life – Indian and English – still Exist” (Naseem Khan, 1980)

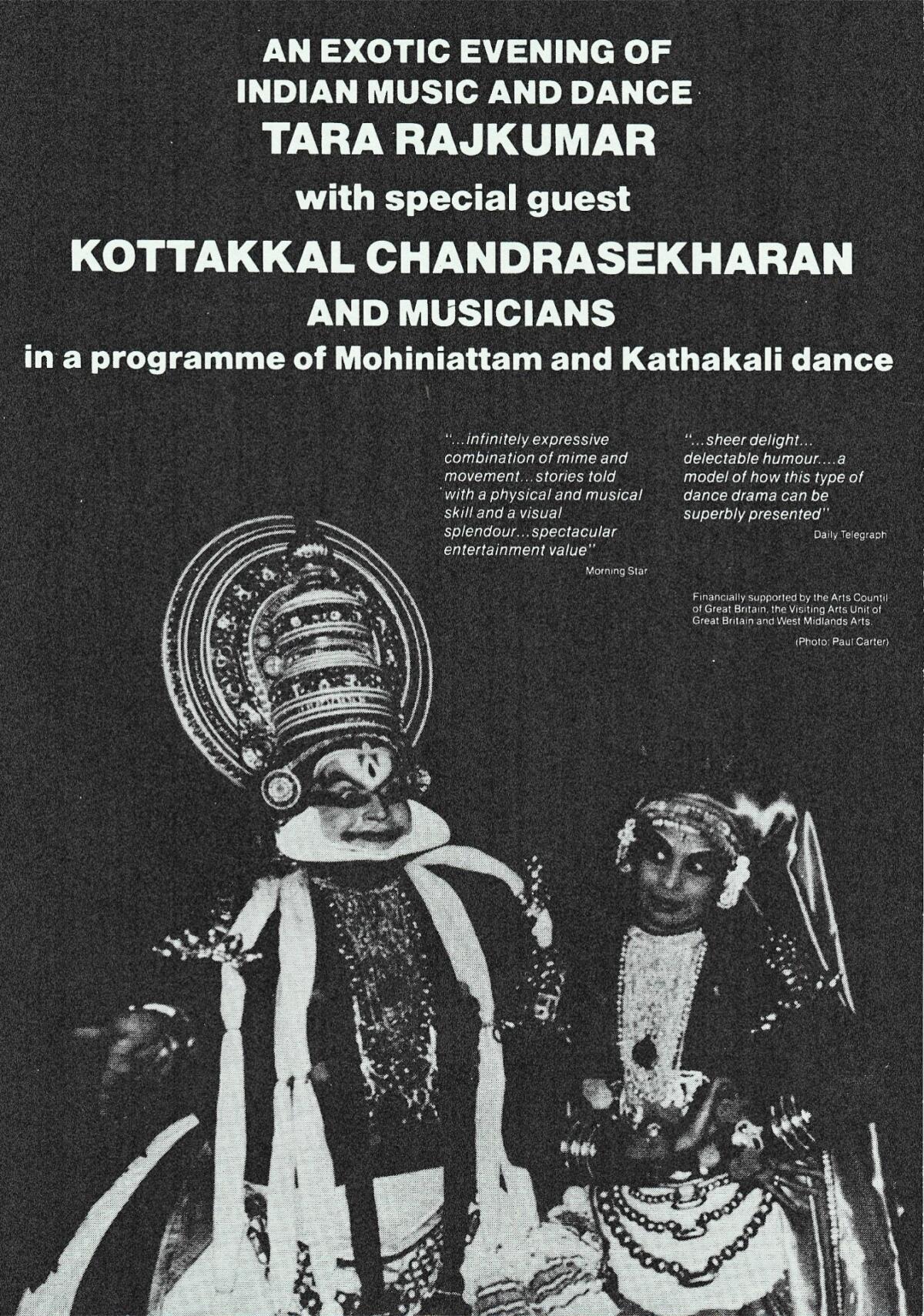

So, when Indians were still considered an “ethnic” minority in the UK, and their dances, variously labelled exotic and folk, how did Tara manage to break the bubble and reach out to the generation to come? The process sure was long and tedious, but it was a start to being offering workshops and little insights into a world that exists beyond the known. Even thinking of Tara presenting her first repertoire and a workshop with an “exhilarating yet exhausting lesson” on Kathakali, makes it almost impossible to imagine how she succeeded in leading the way to what Akademi has become today.

It certainly is the foundation to Akademi’s endeavours in creating a space for Indian classical dance to flourish in the country. If there is one thing these archives have given us access to, it is reading the transformative power of keeping at things and tiding over hierarchies of language and structure to recreate dance forms all over again. Archives are the peek into that past, with the feet firmly walking towards the future.

Watch this space for more blogposts from our wonderful Heritage Project volunteers.

References:

Thobani, Sitara (2017). Indian Classical Dance and the Making of Postcolonial National Identities: Dancing on Empire’s Stage. Taylor and Francis. Available at: https://www.taylorfrancis.com/books/9781315387345

Quotes from the archives:

Bladen, Anthony (June 12, 1981) Eloquent Language of the Dance. Somerset County Gazette.

Khan, Naseem (April 13, 1980) Indian Dancing, Ealing Style. The Sunday Times Magazine issue on “Dance”. Pages 50-51

Massey, Reginald (September 1982). Eastern Delights. Dancing Times. Pp.905.

Archives:

Pictures:

Pic 1: King, Jane (February 1982). ILEA Centre for Learning Resources and the Academy’s Exhibition of India and its Classical Dances held in October 1981 – A Report.

Pic 2: Massey, Reginald (September 1982). Eastern Delights. Dancing Times. Page 905.

Pic 3: Poster of a Kathakali Performance.

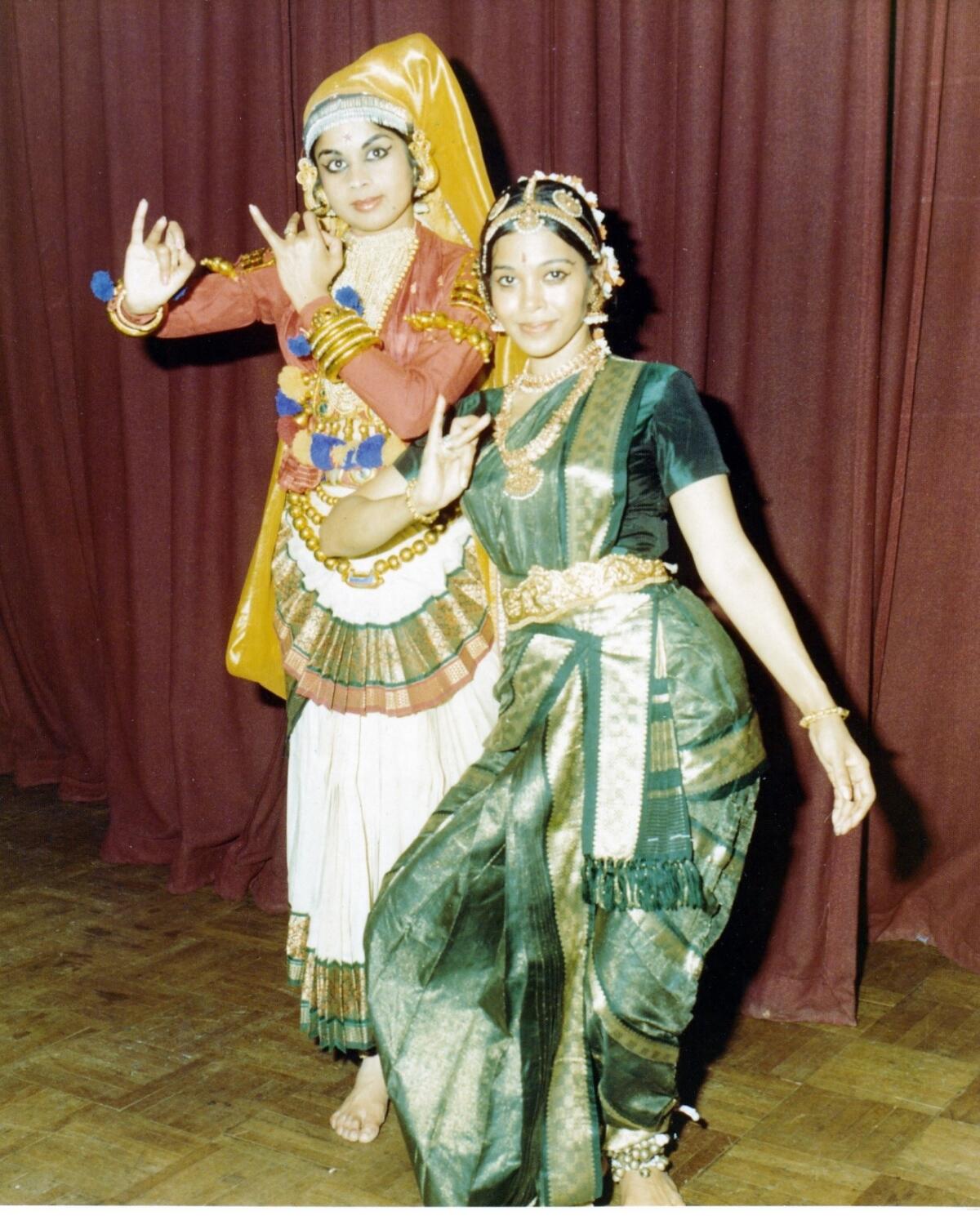

Pic 4: Tara Rajkumar and Rati Karthigesu (8 April 1979). Bhavan event.

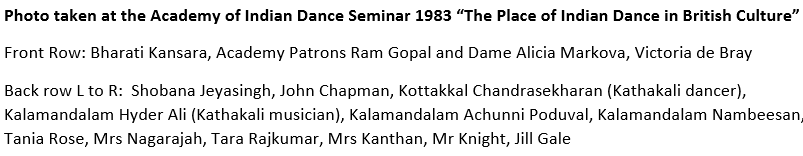

Pic 5: Picture taken at the Academy of Indian Dance Seminar (1983).

Pic 6: Khan, Naseem (April 13, 1980) Indian Dancing, Ealing Style. The Sunday Times Magazine issue on “Dance”. Page 51.